Tiger Rag

| "Tiger Rag" | |

|---|---|

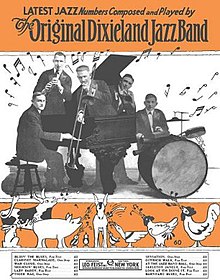

Sheet music for "Tiger Rag" as recorded by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band (1918) | |

| Instrumental by The Original Dixieland Jazz Band | |

| Released | 1917 |

| Recorded | 1917 |

| Genre | Dixieland |

| Label | Aeolian-Vocalion |

| Composer(s) | Eddie Edwards, Nick LaRocca, Henry Ragas, Tony Sbarbaro, Larry Shields |

| Lyricist(s) | Harry DeCosta |

| Recording | |

Performed by the Dixie Players of the United States Air Force Heritage of America Band | |

"Tiger Rag" is a jazz standard that was recorded and copyrighted by the Original Dixieland Jass Band in 1917. It is one of the most recorded jazz compositions. In 2003, the 1918 recording of "Tiger Rag" was entered into the U.S. Library of Congress National Recording Registry.[1][2]

Background

[edit]The song was first recorded on August 17, 1917, by the Original Dixieland Jass Band for Aeolian-Vocalion Records (the band did not use the "Jazz" spelling in its name until 1917).[3] The Aeolian-Vocalion sides did not sell well because they were recorded in a vertical-cut format which could not be played successfully on most contemporary phonographs.

But the second recording on March 25, 1918, for Victor, made by the more common lateral-cut recording method, was a hit and established the song as a jazz standard.[4] The song was copyrighted, published, and credited to band members Eddie Edwards, Nick LaRocca, Henry Ragas, Tony Sbarbaro, and Larry Shields in 1917.[5]

Authorship

[edit]"Tiger Rag" was first copyrighted in 1917 with music composed by Nick LaRocca. In subsequent releases, the ODJB members received authorship credit. This authorship has never been challenged legally. According to author Frank Tirro,

But even before the first recording, several musicians had achieved prominence as leading jazz performers, and several numbers of what was to become the standard repertoire had already been developed. "Tiger Rag" and "Oh, Didn't He Ramble" were played long before the first jazz recording, and the names of Buddy Bolden, Jelly Roll Morton, Bunk Johnson, Papa Celestin, Sidney Bechet, King Oliver, Freddie Keppard, Kid Ory, and Papa Laine were already well known to the jazz community.[6]

Other New Orleans musicians claimed that the song, or at least portions of it, had been a standard in the city before it was recorded. Others copyrighted the melody or close variations of it, including Ray Lopez under the title "Weary Weasel" and Johnny De Droit under the title "Number Two Blues". Members of Papa Jack Laine's band said the song was known in New Orleans as "Number Two" before the Dixieland Jass Band copyrighted it. In one interview, Laine said that the composer was Achille Baquet.

In his book Jazz: A History, Frank Tirro states, "Morton claims credit for transforming a French quadrille that was performed in different meters into ‘Tiger Rag’".[7]

The Italian musicologist Vincenzo Caporaletti has shown how the authorial self-attributions of Jelly Roll Morton are not reliable, by means of an analysis conducted on the first complete transcription in musical notation of Morton's Library of Congress performances (1938) with conclusions defined by Bruce Boyd Raeburn "justifiably compelling" on a scientific level.[8] Furthermore, Caporaletti has accurately identified the "floating folk strains" that Nick La Rocca assembled to create "Tiger Rag".[9]

According to writer Samuel Charters, "Tiger Rag" was worked out by the Jack Carey Band, the group which developed many of the standard tunes that were recorded by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band.[10][11]

According to Tirro, the song was known as "Jack Carey" by the black musicians of the city. "It was compiled when Jack's brother Thomas, 'Papa Mutt', pulled the first strain from a book of quadrilles. The band evolved the second and third strains in order to show off the clarinetist, George Boyd, and the final strain ('Hold that tiger' section) was worked out by Jack, a trombonist, and the cornet player, Punch Miller."[6]: 170

Other recordings

[edit]

After the success of the Original Dixieland Jass Band recordings, the song gained national popularity. Dance band and march orchestrations were published. Hundreds of recordings appeared in the late 1910s and through the 1920s. These include the New Orleans Rhythm Kings version with a clarinet solo by Leon Roppolo. Archaeologist Sylvanus Morley played it repeatedly on his wind up phonograph while exploring the ruins of Chichen Itza in the 1920s. With the arrival of sound films, it appeared on soundtracks to movies and cartoons when energetic music was needed.

"Tiger Rag" had over 136 versions by 1942.[12] Musicians who played it included Art Tatum, Benny Goodman, Frank Sinatra (in a version with lyrics), Duke Ellington, Bix Beiderbecke, and Louis Armstrong, who released the song at least three times as a 78 single, twice for Okeh in 1930 [13] and 1932,[13] and for the French arm of Brunswick in 1934.[14] A Japanese version was recorded in 1935 by Nakano Tadaharu and the Columbia Rhythm Boys.

The Mills Brothers became a national sensation with their million-selling version in 1931.[15] In the same year the Washboard Rhythm Kings released a version that was cited as an influence on rock and roll. During the early 1930s "Tiger Rag" became a standard show-off piece for big band arrangers and soloists in the UK, where Bert Ambrose, Jack Hylton, Lew Stone, Billy Cotton, Jack Payne, and Ray Noble recorded it. But the song declined in popularity during the swing era, as it had become something of a cliché. The Light Crust Doughboys recorded a 1936 western swing version of "Tiger Rag" to wide success in the Gene Autry movie Oh! Susanna. Les Paul and Mary Ford had a hit version in 1952. Charlie Parker recorded a bebop version in 1954, the same year it appeared in the MGM cartoon Dixieland Droopy. In 2002, it was entered into the National Recording Registry at the U.S. Library of Congress.

It is the 32nd most recorded song from 1890 to 1954 based on Joel Whitburn's research for Billboard.[16]

A variant of the song is used by the Royal Thai Armed Forces as a "running march" during its military parades.[17]

A fight song in sports

[edit]"Tiger Rag" is often used as a fight song by American high school and college teams which have a tiger for a mascot. "Tiger Rag" is LSU's pregame song, which was first introduced in 1926. The Louisiana State University Tiger Marching Band performs it on the field before every home game and after the Tigers score a touchdown.

The Auburn University Marching Band also plays "Tiger Rag" as part of its pre-game performance before all home football games. The smaller pep band that plays for basketball games plays it just before the start of each half, timed so that the final note of the song is played as the horn sounds when the "game clock" counts down to triple-zeroes before each half.

The University of Texas at Dallas adopted "Tiger Rag" as its first official fight song in 2008.[18]

The Massillon Tiger Swing Band of Massillon, Ohio began playing "Tiger Rag" at Massillon Washington High School Tigers football games in 1938 when the team was coached by Paul Brown. It has been a Tiger tradition in Massillon ever since.[19]

The Cuyahoga Falls Tiger Marching Band plays Tiger Rag after the team scores the extra-point, as well as during their famous "Double Tiger Lines" drill, started in 1968.

"Tiger Rag – The Song That Shakes the Southland" is Clemson University's familiar fight song since 1942 and is performed at Tiger sporting events, pep rallies, and parades. A version has been arranged for the carillon on Clemson's campus.

It also has been played by Dixieland bands at Detroit Tigers home games and was popular during the 1934 and 1935 World Series.

Cover versions

[edit]"Tiger Rag" became a jazz standard that was covered by Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, Ted Lewis, Joe Jackson, the Mills Brothers,[20] and others. Notable recordings include:

- Louis Armstrong – Louis Armstrong in Scandinavia Vol. 4, Stockholm, January 16, 1959[15]

- Louis Armstrong – New York, May 4, 1930[15]

- The Beatles – Get Back/Let It Be sessions, 1969[21]

- Bix Beiderbecke – Richmond, Indiana, June 20, 1924[15]

- Duke Ellington – New York, January 8, 1929[15]

- Benny Goodman with Mel Powell – New York, August 29, 1945[15]

- Andre Kostelanetz[15]

- Liberace[15]

- Glenn Miller[15]

- The Mills Brothers – New York, October 3, 1931[15]

- Ray Noble[15]

- Mark O'Connor with Wynton Marsalis – In Full Swing, New York, August 26–30, 2002[15]

- Original Dixieland Jazz Band – New York, March 25, 1918[15]

- Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Lennie Tristano – Bands for Bonds radio broadcast, New York, September 20, 1947[15]

- Les Paul and Mary Ford – Oakland, New Jersey, c. 1951[15]

- Nicholas Payton – Dear Louis, New York, September–October 2000[15]

- Raymond Scott – At Home with Dorothy and Raymond, New York, November 3, 1956[15]

- Art Tatum – New York, March 21, 1933[15]

- Paul Whiteman – "The New Tiger Rag", New York, July 25, 1930[15]

- Asleep At The Wheel with Old Crow Medicine Show, 2015.[22]

In popular culture

[edit]An instrumental portion is used in the soundtrack of Bimbo's Initiation (1931),[23] and a vocal version of "Tiger Rag" can be heard in another Betty Boop cartoon, Betty Boop and Grampy (1935). This particular version was later used in a brief scene in the Ren & Stimpy "Adult Party Cartoon" episode "Fire Dogs 2" (2003).[24] That version of the song was also used in a commercial for Xbox 360 during its launch in 2005.[25] The song is often heard in the "Ma and Pa Kettle" movie series. It also plays a prominent part in the film "Tucker: The Man and His Dream."

The song is mentioned in David Bowie's song "Watch That Man" (1973).[26]

References

[edit]- ^ "Tiger rag". Loc.gov. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ ""Tiger Rag" - The Original Dixieland Jazz Band (1918)" (PDF). Loc.gov. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ Brunn, H. O. (1977). The Story of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-70892-2.

- ^ Jack, Stewart (2005). The Original Dixieland Jazz Band's Place in the Development of Jazz. New Orleans International Music Colloquium. New Orleans.

- ^ "Original Dixieland Jass Band". Red Hot Jazz Archive. 26 April 2020.

- ^ a b Tirro, Frank (1977). Jazz: A History. New York City: W. W. Norton. p. 157. ISBN 0-393-09078-7.

- ^ Blesh, Rudi (1958). Shining Trumpets: A History of Jazz (2 ed.). New York City: Knopf. p. 191.

- ^ Caporaletti, Vincenzo (2011). Jelly Roll Morton, the Old Quadrille and Tiger Rag. A Historiographic Revision. Lucca: Libreria Musicale Italiana. p. 49.

- ^ Caporaletti, Vincenzo (2018). ""Tiger Rag" and its Sources: New Interpretative Perspectives". Revue d'Études du Jazz et des Musiques Audiotactiles (1): 1–34. ISSN 2609-1690. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Charters, Samuel B. (1963). Jazz: New Orleans, 1885–1963 (Revised ed.). New York: Oak Publications. p. 24.

- ^ "Jack Carey (1889-1934)". Red Hot Jazz Archive. 26 April 2020.

- ^ "Jazz Standards Songs and Instrumentals (Tiger Rag)". Jazzstandards.com.

- ^ a b "Stardom: Louis Armstrong On His Own (1929 - 1932)". Archived from the original on 2011-08-22. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ "Swinging In the Thirties (1932 - 1942)". Archived from the original on 2013-11-07. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Gioia, Ted (2012). The Jazz Standards: A Guide to the Repertoire. New York City: Oxford University Press. pp. 434–436. ISBN 978-0-19-993739-4.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2022-01-06. Retrieved 2022-01-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "โน้ตเพลงวงโยธวาทิต (Military Band) โน้ตเพลงสำหรับวงโยธวาทิต เพื่อใช้บรรเลงในงานราชพิธี งานพิธีการทั่วไป และ งานบรรเลงเดินแถวสวนสนาม".

- ^ "Worth Singing About: Comets Get a Fight Song". UT Dallas News Center. 2008-09-29. Retrieved 2021-09-21.

- ^ Wenzel, Robert (10 June 2004). "History of the Tiger Swing Band". Archived from the original on 2004-06-10. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ "Original versions of Tiger Rag written by Nick LaRocca, Eddie Edwards, Henry Ragas, Tony Sbarbaro, Larry Shields". Secondhand Songs.

- ^ "Get Back/Let It Be sessions: complete song list". beatlesbible.com. 5 February 2011.

- ^ "Asleep at the Wheel - Tiger Rag (with Old Crow Medicine Show)". 16 April 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ Scoggin, Lisa (2023). The Intersection of Animation, Video Games, and Music: Making Movement Sing. p. 66.

- ^ "Max Fleischer". Lambiek.net. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ "Xbox 360 Jump in Commercial - Standoff". YouTube. 3 July 2009.

- ^ O'Connell, John (2019). Bowie's Bookshelf The Hundred Books that Changed David Bowie's Life. Gallery Books. p. 72.